"I do not remember to have seen in Italy a composition so beautiful or pictorial as this glorious range of the Adirondacks"

- Thomas Cole

A Paradox

As to be expected with the Adirondacks, Stoddard's depiction of "wilderness" represents a paradox in and of itself. If we accept that wilderness truly is "untrammeled by man" (as suggested by the New York Constitution), and we know that Stoddard has to stand in a certain place in order to take a photograph of that place, then can we count the "wild" subjects of Stoddard's photos as actually wild? By going to any wilderness location to snap a picture, Stoddard would render that land no longer "untrammeled by man." Thus in some ways, Stoddard's documentation of the wild Adirondacks actively defies the traditional conception of "wilderness."

luminism

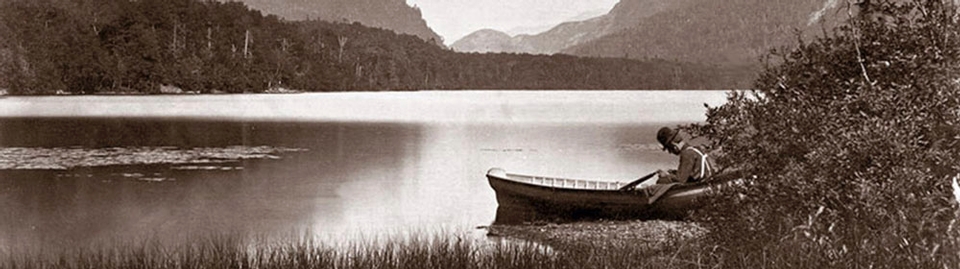

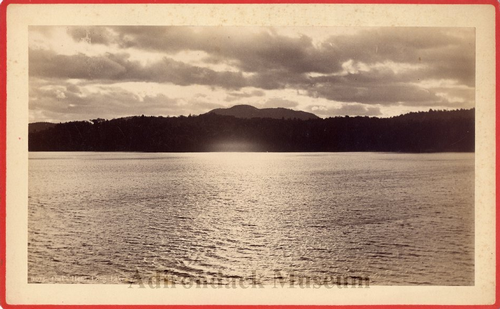

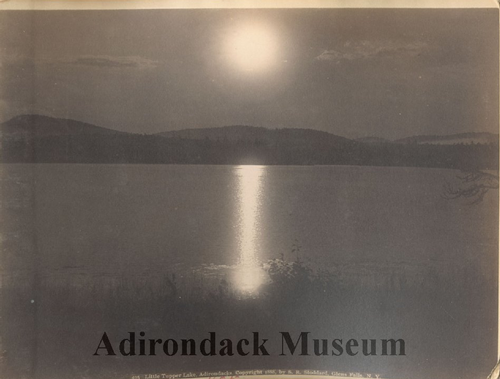

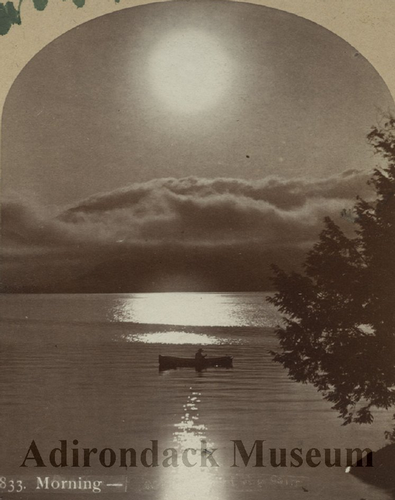

Many of Stoddard's photographs of the Adirondack wilderness share techniques and styles with other romantic, 19th-century artists. One such quality is referred to as luminism. Luminism often emphasizes the use of natural light and is characterized by, especially in the case of Stoddard, "horizontal order, balanced tonal contrasts, open surfaces of silvery water, and low sunlight faced centrally across the views" (William Crowley, 16). In the photographs below, Stoddards use of a longer exposure in a low light situation added to the romantic effect of these photographs by creating an idyllic feeling surrounding the water. Especially in Little Tupper Lake and Morning, we peaceful stillness in the water, which futhers the romanticization of the Park in these images.

Owle's Head, Long Lake

photo: the adirondack museum

Little Tupper Lake, Adirondacks

Photo: the adirondack museum

Morning

Photo: the adirondack museum

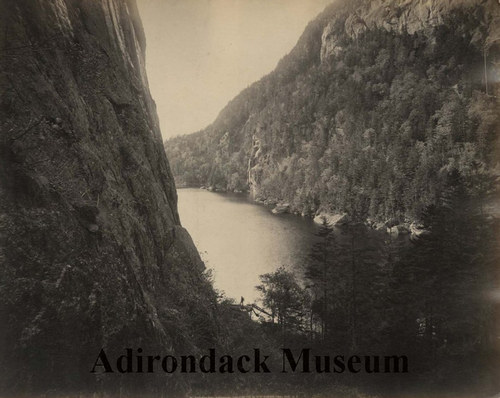

The sublime

In the style of Transcendentalists and Romantics before him, Stoddard imbues his images with an awe-inspiring aura of total apprehension in the face of nature's great power. In his photo "Avalanche Lake" (pictured below), Stoddard captures the silohuette of a lone hiker, appearing miniscule and powerless amid the dark, yet glowing natural beauty around him. The gray, imposing cliffs, which follow strong lines that disappear at a bend in the river, hang ominously from edges of the frame, as if they are encroaching on the light and peaceful cove. Despite the fear conjured up by the scene's dark colors and eerily commanding rockfaces, there is still an element of beauty in the image. In a word, the scene represents the sublime. It serves as a stark reminder of the indominatable power of the wild, particularly in contrast to man's apparent diminution.

Avalanche Lake, Adirondacks.

Photo: the adirondack museum

A description of the scene in Stoddard's own words:

"Its cold waters have rocks that rise precipitously on either

side, perpendicular at places, at others rounding smoothly for

1,000 feet upward, naked save where a hardy shrub or tree has

found lodgment in some clift [sic]. It is Adirondack Pass, but

one must scale mountain heights to compass it, or take boldly

to the water. At one place a rock rises perpendicularly for

many feet, seemingly to present an impassable barrier; but to

the initiated a way has always been open."

(The Magic Lantern Society of the United States and Canada, 2009)

The element of the sublime is a recurrent theme throughout Stoddard's images of the wild. He focuses a lot on rocky cliffs, impossibly serene rivers, and a foreboding contrast between light and dark. To Stoddard, at least, the Adirondacks are largely defined by the breathtaking wilderness that resides inside it. Much of Stoddard's efforts towards the end of his career centered around protecting that breathtaking wilderness, but also on sharing it. This depiction of the sublime allowed Stoddard to produce awe-inspiring images, evoking more emotion and amazement in his viewers, especially regarding the Adirondack wilderness landscape.

Ausable Chasm - Up the River from Table Rock

photo: the adirondack museum