Logging

Stoddard frequently documented the massive logging that was occuring in the Adirondack in the late 1800's. In his magazine Stoddard's Northern Monthly, which he released monthly from 1906-1908, he exhibited strong, though sometimes flawed, opposition to this industry. He posited that clearing away forests was often the cause of shallower waters in the summer, because of a more rapid evaporation process on the denuded land. For Stoddard, the increased dryness of the land meant more forest fires, and more destruction of his precious Adirondacks. To quell this devastation, Stoddard sought to photograph the industry of logging, often highlighting the barren path in its wake.

When the question of constitutional protection of the park came about, Stoddard explicitly stated that he felt there was little to no convincing argument showing that "the position taken against the proposed opening of the Forest Preserve in the interests of lumber and pulp wood [was] wrong" (Stoddard's Northern Monthly, 1908, 7). It was clear to him that the park was in danger, and needed to be protected.

The Choppers

Photo: The Adirondack museum

This photograph, taken around 1898 and entitled The Choppers, depicts Adirondack lumberers at work during the frigid winter months. Though less disturbing than other photos of Stoddard's as it somewhat glorifies the rugged woodsmen, The Choppers serves to show the number of trees that were removed in a certain tract of land once a lumbering company began working. Although it was terrifying for Stoddard and others to see their beloved forests ravaged, this old fashioned style of logging, with axes and saws, does not compare to the more modern, efficient styles that are removing timber today.

Log Jam near Finch, Pruyn & Company

photo: the adirondack museum

In one of Stoddard's editions of Stoddard's Northern Monthly, the artist provides us with a number of statistics regarding the logging situation in the Adirondacks in 1906. He claims that this year the logging industry produced more lumber than ever before, including approximately 40 billion feet of lumber. The above photo shows a log jam, which occurred frequently during the technique of sending timber down a river towards the mills at which it would be processed and proved to be dangerous, or even fatal, to those lumbermen who needed to find the source of the jam and remedy it. These jams were not just dangerous to the humans who initially created them, however; they were also detrimental to the surrounding environment because they caused erosion and other disruptions to the natural habitat.

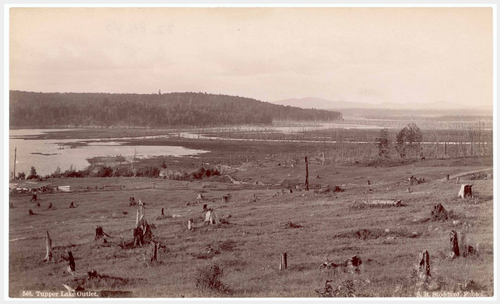

Tupper Lake Outlet

Photo: new york state museum

This photograph of Stoddard's, Tupper Lake Outlet, provides an example of the barren lands that were left behind as a result of the incessant logging during this time. As mentioned above, Stoddard refers to the danger of this kind of clear-cutting in his edition of Stoddard's Northern Monthly from Aprill, 1908. He describes how the sun dries out a patch of untimbered land more quickly than it does a timbered one. The dryness of the underlying vegetation can then lead to more frequent fires, only reinforcing the logging that has already been done. Furthermore, while reforestation would provide tree cover to repair the damages ecosystem, Stoddard believes that it will take thousands of years before the new growth forests will return back to their quazi-original state.

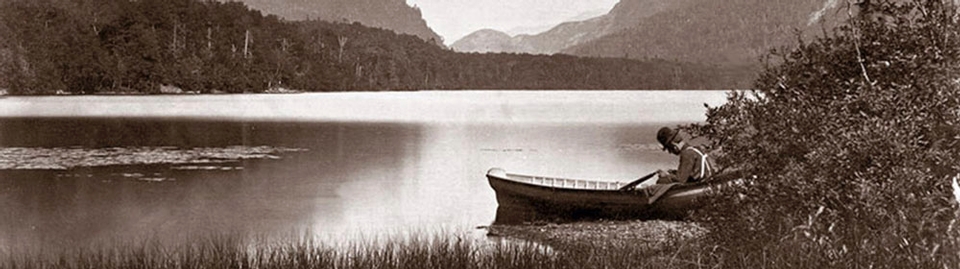

Lumbering Logs by an Adirondack Stream

Photo: the adirondack museum

The above photograph serves as an example of Seneca Ray Stoddard's tendency to contrast wilderness with industry. We see what would be a beautiful, almost romantic woodland scene was it not tainted by bending and lumbered trees. As discussed further HERE, Stoddard often spoke of his fondness for nature in his writing, and documented it through his photography. In many of his photographs, he used this love of the land and his romantic photography abilities in order to create a stark and disturbing contrast, highlighting the ways in which industry ruins the landscape.

Dams

"There exists to-day hardly one important lake or stream in the Adirondacks that has not been tampered with, dammed in the name of soulless utility with a result fairly expressed by a different spelling of the word..."

-Seneca Ray Stoddard, "The Head-Waters of the Hudson," 1885

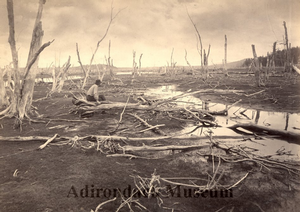

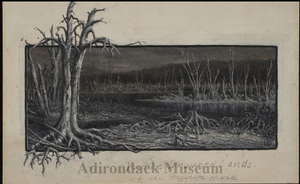

In order to mitigate the log jams that Stoddard ever so lovingly documented and facilitate the logs' movement towards the mills where they would be processed, dams were often built along the rivers, lakes, and streams that were a part of this business procedure. Stoddard felt, as he did towards most industry, strongly opposed to this tampering, and documented the flooded landscapes. These sad, downtrodden images represent the aftermath of human interference in a natural space. The second image, Drowned Lands of the Lower Raquette, feels like a romantic image, with glassy, serene water and beautiful lighting, but is contrasted by the tortured and barren branches covering the scene. In his paintings of this drowned scene, Stoddard looked to further depart from this typical beautiful landscape and focus heavily on the distorted and endangered landscape caused from the presence of the dams and the surrounding deforestation. (Horrell, 85)

In Stoddards article, "The Head-Waters of the Hudson," written in 1885, he refers to the effects of logging on the Hudson River and its related tributaries. He compares the decimation of the Adirondack watershed to someone attempting "to blast away the rock which the Niagra pours," (Horrell, 63) in order to make monetary or industrial gains. Finally, he provides a beautiful description of the Adirondack landscape, including glistening rivers and rippling lakes, and leaves us with the question; "This is our heritage; shall our children have reason to say we were unworthy of the trust?" (Horrell, 64). With this final statement, he challenges us, and the New York State legislature, to appreciate and preserve the Adirondack Forest Preserve.

In the Drowned Lands of the Lower Raquette In the Drowned Lands of the Raquette River

PHOTO: The adirondack Museum MONochrome oil on board: the adirondack museum

Though not a policy maker by any means, Stoddard actually had a few suggestions of his own regarding the protection of the Adirondacks' magnificent watershed and the regions surrounding it. In the 'Greeting' of the 1891 edition of his guidebook, The Adirondacks: Illustrated, Stoddard presented two amendments to the current protection of the Park. As is evident in these suggestions, Stoddard definitely shared the opinions of many other environmentalists of this time, including the famous Verplanck Colvin, but is lacking in the language used in his amendments. In other words, his sentiment is clear, but the vague word usage and regulations would not hold up against the unbelievable economic interested we see in the park today. Stoddards first amendment prosposed the enactment of:

"a law prohibiting forever the cutting of any evergreen tree except with the approval of competent authority under the government, on any land in New York State lying 1,800 feet above tide" (The Adirondacks: Illustrated, VII-VIII).

Stoddard was not concerned about the economic endeavors of loggers, and really any other industry, and seemed to assume that they could sustain themselves without access to the resources of the Forest Preserve lands.

The second suggestion of Stoddard's is a bit simpler. He proposes that the majority of the Adirondack watershed:

"should be under the control of the State, and would be cheap at almost any price, now, before irreparable injury is done" (The Adirondacks: Illustrated, VI).

Stoddard understood that the only way to create withstanding regulations regarding the protection of the Park was to have State control over the land. Private owners, in general, could not be trusted not to overstep their bounds. Further, he understood the timeliness of this matter, in that human and industry induced damaged would not be corrected for a number of years, if ever.

You can read the 'Greeting' from The Adiriondacks: Illustrated in full on our page about the guidebook by clicking HERE.

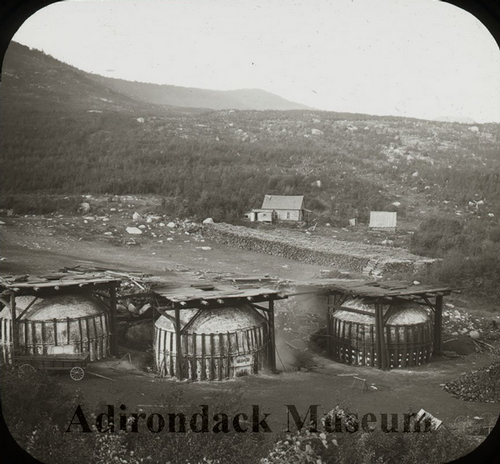

Charcoal Kilns

During this time of booming industry in the Adirondacks, many conical charcoal kilns were erected and used to convert lumber into charcoal, which was utilized quite frequently in the tanning industry. In two of the images below, we can observe the destruction and clearing of significant portions of land surrounding where these kilns were placed. The smoke arising from the kilns in the first image further represents the toxification of the environment by human industry.

Charcoal Kilns, The Narrows, Chateaugay Lake

PHOTO: the adirondack museum

Charcoal Kilns

Photo: The adirondack Museum

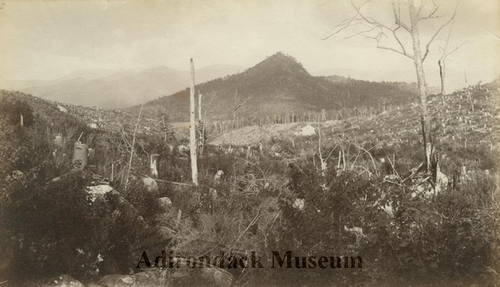

Track of the Charcoal Burners

photo: the adirondack museum

Though the origins of this photograph are unclear aside from the fact that it was taken by Stoddard, the title suggests that it depicts the reprecussions of a fire caused by these charcoal kilns. In this photograph, it is clear to see that the consquences of human action in the Park are often long-lasting or even irreparable.

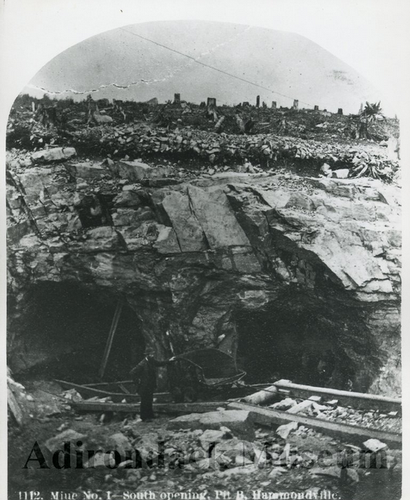

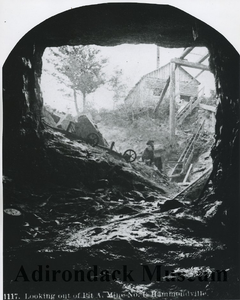

Mining

Looking out of Pit A., Mine No.1, Hammondville Mine No.1 - South opening, Pit. B., Hammondville

Photo: the adirondack museum photo: the adirondack museum

Mining is obviously one of the most intrusive forms of industry in the Adirondacks, in that it often involves excavating and destroying huge swaths of land in search of ore, minerals, and other products. Seneca Ray Stoddard does not focus heavily on the impacts of mining on Adirondack land in his writings, possibly because mining was less widespread than logging was at the time. However, he did photograph these areas, creating ominous and intimidating images of this invasive process.