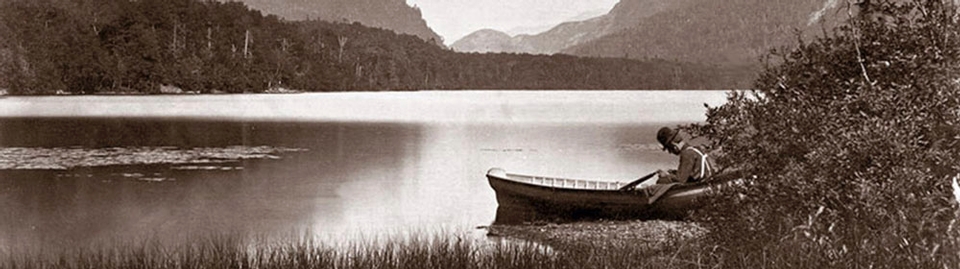

As the Adirondacks gained more popularity as a home, vacation destination, and industry magnet, the region came to be defined and re-defined by its the ever-changing inhabitants. Through his widely disseminated photography, Stoddard played an integral role in the cultivation of those definitions. Stoddard, who imbued each piece with his own Romantic perspective on the Adirondacks, "shaped how thousands of potential visitors thought about and would view the region" (Horrell, 141). By virtue of his chosen field's very public nature, everything that Stoddard produced, from written publication to photo print, was encountered (and well received) by exactly those who might one day be lured by his enticing artwork to visit the Adirondacks in person. While no direct link between Stoddard's work and subsequent visitors to the Park can be made, it is undeniable that Stoddard was a huge "part of the network that developed and transformed the region" (Horrell, 132). From simply garnering attention for the Adirondacks to actually providing detailed maps and plans that visitors could follow all the way there, Stoddard encouraged tourists to come to the Adirondacks and actually shaped their perceptions of what they would find when they got there.

Stoddard's work is known to be influential in part because it reached such an incredibly wide audience. Beyond his own publications, much of Stoddard's work was reviewed in the popular press by papers like Harper's Weekly, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, The Philadelphia Photograph, and even The New York Times. His photographs were exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. Throughout his career, Stoddard created thousands of images and reproduced and sold those images in numbers reaching the tens of thousands. He made stereographs, individual photographs, souvenir postcards, and hand-tinted slides--not even counting the multitudes of maps and collections he put together. Oftentimes he would give his photos to Adirondack Guides who would sell them to tourists or else incoporate them into hotel brochures whose distribution reached farther than the Blue Line alone. Even still, his work gained in popularity after his death in 1917--flip through the textbooks for this course alone and you're guaranteed to find at least one Stoddard photo in every chapter. As historian Jeffrey Horrell so clearly puts it, Stoddard "documented, and through his interpretation, shaped how thousands of potential visitors thought about and would view the region" (Horrell, 141).

Much of Stoddard's legacy resides in the way that he presented the Park as both a land to be protected and a land to be enjoyed. He fought to maintain the wilderness he knew so well, but also adamantly believed that anyone should be able to experience the natural phenomena the wild lands have to offer. In true spirit of the grand Adirondack experiment, Stoddard's work in the Adirondacks searches for the balance between man and mountain, celebration and conservation. It seems that Stoddard found no such answer, but perhaps here we should be reminded that just as wilderness can be distinctly interpreted by each unique onlooker, so can his art that aimed to document it.