Despite being known for his photographs depicting the wild Adirondack landscape, much of Stoddard's work actually focused on the people that dotted the Adirondack landscape. Whether guides, residents, tourists, native New Yorkers, or otherwise, Stoddard explored the ways in which the Adirondack's inhabitants (however temporary) related to the land they walked on. By focusing on the interactions between people and landscape, Stoddard visually captured the inception of the tourist industry in the Adirondacks and the budding relationship between its people and its once-peopleless ground.

Residents

The relationship between people and the Adirondacks starts with those who live there, because Adirondack residents are the people who set the precedent for modifying the land for human use. Stoddard comments on this relationship between man and land, as well as between simple homestead and grand Great Camp, through his photographs of the trend-setting Adirondackers.

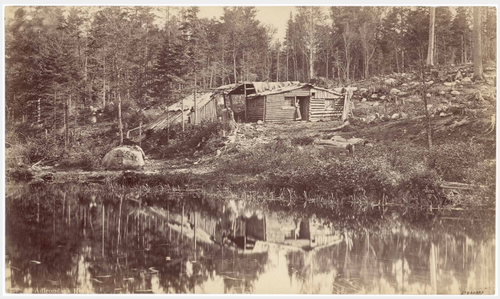

Adirondack Homes

First and foremost, the Adirondacks provided a home base for immigrants, people looking for jobs or new opportunities, or just people looking for a more natural habitat. Following the Beaver Wars and European arrival in the Park (long before, of course, the region became the Adirondack Park), this second wave of more permanent homesteaders began transforming the Adirondacks from a wilderness to a home. By the time that Stoddard was documenting the Adirondacks, much had already changed by way of who was using that Adirondacks and to what ends. But with the continued increase of tourism in the Park (fostered, in large part, by his own publications and promotion of the Park), that change would only grow.

An Adirondack Home

New York State Museum

This photograph, entitled "An Adirondack Home," captures the simplicity of some cabins in the Adirondacks. Surrounded by trees and water, this modest home represents the more moderate (and perhaps more relatable) side of Adirondack living that is so often outshone by the flashy Great Camps and public hotels.

Adirondack Great Camps

At the near opposite end of the spectrum of Adirondack residents lies the Great Camps. Great Camps are renowned for their lavish, yet rustic appearance and are often indicative of their owner's wealth and status.

Great Camps serve as an outlet into the wild natural world while maintaining creature comforts, in a way bringing their inhabitant's close enough to enjoy the Adirondack views, but not close enough to get bit by the Adirondack bugs. Stoddard was often commissioned to take pictures of the Great Camps, like by one-time William West Durant owner of Camp Pine Knot and Sagamore. Stoddard himself admits that the Great Camps (and particularly Camp Pine Knot) were "elegant affairs" and "works of art" that "ke[pt] with their native environment" (Horrell, 103-104). As an appreciator of fine aesthetics (as well as a man in need of an income), Stoddard lauded the Great Camps and viewed them as just another part of the Adirondack scenery which should be celebrated.

The Main Lodge at Sagamore

PHOTO: Stickley Museum

Native American Camps

Of Stoddard's work that includes people, he predominantly features white, wealthy, Americans. Ironically enough, the body of Stoddard's work largely ignores the original Adirondack inhabitants: the Native American tribes that lived off of and around the land. When compared to the majority of his photographs, this picture captures the pronouncced differences in the relationships held between the Native Americans and the Adirondacks as contrasted with the white Americans who most often stayed in Great Camps or hotels and belonged to clubs.

Indian Encampment, Lake George, 1872

New York State Museum

Tourism

Unlike the year-round inhabitants of the Park (or the seasonal, vote-bearing Great Camp owners), many people flocked to the Adirondacks around the turn of the 19th century to experience, in a very temporary and, arguably, diluted way, the paradise that Adirondack Murray raved about and that Stoddard's own photos portrayed as such an enticing destination. These tourists to the Park established a largely different relationship with the land than their more permanent counterparts and Stoddard worked to capture these interactions between tourists and what they viewed as their Adirondack playground.

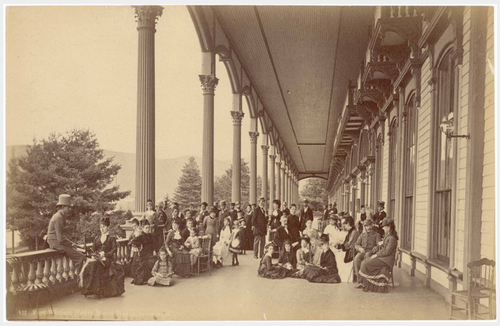

Hotels

Prospect House Lobby

New York State Museum

By the end of the 1800s, Adirondack hotels had become a staple for wealthy tourists seeking a "wilderness" experience, complete with all the luxuries and amenities of their usual standards. In these next few photos, Stoddard documents the ritzy accomodations that Adirondack hotels provided. From fantastically decorated lobbys, as documented in Stoddard's "Prospect House Lobby" pictured above, to the showy hotel exterior, as seen in his "Rogers Rock Hotel" below, the hotels clearly catered to the throngs of wealthy Americans seeking fresh air, stunning views, and respite from increasingly urbanized living. Stoddard's photos of the hotels' manicured lawns stand in stark contrast to those of the region's untamed forests.

Stoddard first used his photographs of hotels as advertisements in his publications, like The Adirondacks: Illustrated, which benefitted both himself and the hotels seeking favorable publicity. Stoddard also sold many of his photographs to hang in their lobbies or populate their informational brochures. Stoddard photographred extensively the Prospect House on Blue Mountain Lake, providing "a sense of the grandeur of the life and comfort afforded a certain group of tourists who wanted the experience of the Adirdonack wilderness, but without unpleasant inconvenience" (Horrell, 98).

Rogers Rock Hotel

NEW YORK STATE MUSEUM

Fort William Hotel plazza from West

New York State Museum

Camping

Those who didn't want (or couldn't afford) to stay at a hotel, might choose instead to experience the wilderness with the help of a practice Adirondack Guide. When compared to those of the Great Camps and hotels, the photographs below demonstrate a very different way to experience the Adirondacks.

Game in the Adirondacks

New York State Museum

The photograph "Game in the Adirondacks" depicts the general experience of guides and tourists gathered around the campfire at night discussing the day's catches and telling their own favorite pieces of lore.

Incidentally, Stoddard invented the technology that allowed this night-time photograph to be taken in the first place.

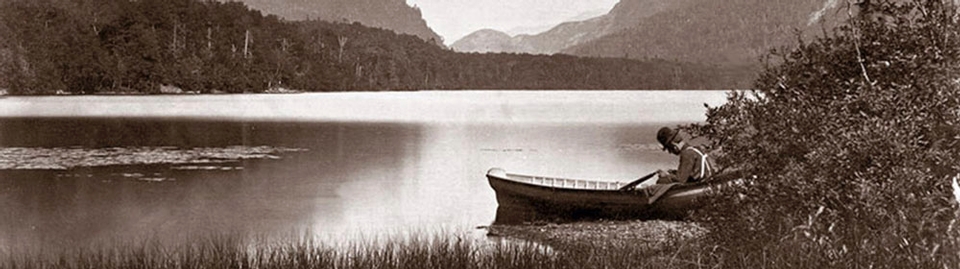

Hunter and Guide in Guideboat

Adirondack Museum

According to the Adirondack Museum, the subjects of the photograph "Hunter and Guide in Guideboat" have been identified as the guide Jack Richards (seated in the bow) and his hunting companion Edward Augustus McAlpin. The scene is believed to be staged--used to represent an action rather than depicting the naural action itself. With this photo, Stoddard manipulates the audience into seeing the simultaneous beauty of the profession (it's a moving composition, no?) as well as the destruction (think focal point: dead deer!) that the job sometimes left in its wake.

Despite the increased foot traffic that guides brought to more remote portions of the Adirondacks, Stoddard believed that Adirondack guides "added an interesting dimension to the lore of wilderness life in the Adirondacks" (Horrell, 102). It seems that Stoddard often struggled between fighting to maintain the wild character of the Adirondacks and wanting people to appreciate and experience the beauty of the landscape--a paradox evident throughout the Park as well as throughout this website.

In any case, the photo, as well as the life of the Adirondack guide that the photo represents, add to ever-growing Adirondack narrative--a piece of Stoddard's own understanding of the Adirondacks that came to be absorbed into that of the public's growing perception of the region.

For more information on guideboats, check out our classmates' page on Adirondack guideboats!

Transportation

Along with increased tourism came the transportation infrastructure to support those tourists. The Adirondacks were slowly transitioning from an exclusive, remote, mostly inaccessible space to a prime vacation spot for the middle and upper classes. When the onset of technology finally reached the North Country, the Adirondacks were suddenly a much more viable vacation spot for more and more people. The Adironacks soon became accessible by rail, boat, carriage, and, eventually, automobile. The introduction of these technologies forever changed the supposed "forever wild" integrity of the land--by introducing railroads, highways, and all the disturbances that accompany those infrastructures, the remote, Blue Line territory no longer seemed quite so remote. Tourism had, in large part, brought about and benefitted from the advent of the automobile and the integration of these technological breakthroughs into the Adirondacks. In conjunction with the "distance tables, routes, time tables, fares to different points, and maps" that Stoddard included in The Adirondacks: Illustrated, people wishing to visit the Adirondacks were well equipped to find their way into the wild Blue Line territory (Horrell, 94).

Rails

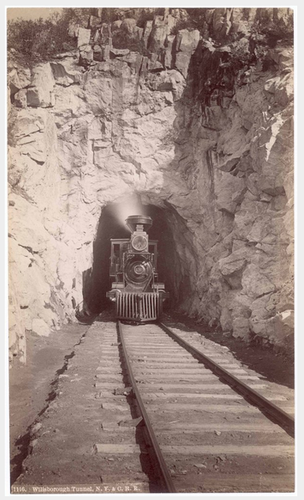

Willsborough Tunnel

New York State Museum

The extensive railroad system throughout the U.S. reflectd the growing desire for fast and comfortable travel--and the Adirondacks were no exception. Because the Adirondacks catered to both industry and tourism, the railroads were often multifunctional. Although originally intended to support resource-based industries like mining and logging, railroads eventually came to "pla[y] an integral rol[e] in realizing the needs of the ever-increasing numbers of tourists" (Horrell, 127).

The aesthetic of Stoddard's "Willsborough Tunnel" also makes an important point about the tension between people and wilderness: at its center stands this man-made monstrosity, puffing steam and barrelling unceremoniously forward, surrounded by a stoic, rocky, natural wonder that does not fail to make that man-made monstrosity seem small. The juxtaposition of man and nature in this photo is frightening--reminding us of man's power to blast holes in mountains in order to keep moving forward, but also that those same mountains are immeasurably more powerful than our tracks.

Ships

As more and more people found reason to travel further and further into the Park, the Adirondacks became ever more accessible by a variety of transportation mechanisms. The Horicon, for one, was a steamboat operating mainly out of Lake George and was used to ferry its passengers to and from surrounding islands or shorelines. Although steamboats like The Horicon did not require highways or railroad tracks, they enabled visitors to reach further into the Park than ever before--slowly but surely allowing humans to encroach on wilderness once inaccessible except by guideboat or on foot.

Horicon at Crosbyside, Lake George

New York State Museum

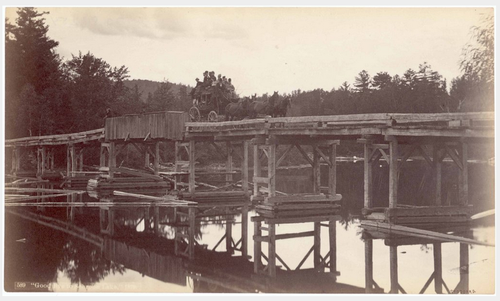

Carriages

While carriages and the predominantly dirt roads they drove on may not have had the highest impact of all the transportation systems, the infrastructure needed to support carriages was still quite extensive. In "Goodbye to Schroon Lake" Stoddard captures a sizable, man-made bridge connecting two sides of a water body for human use. While the bridge does good by humans, structures like it opened up more of the wilderness to development and exploitation. The Adirondacks, once renowned for their inaccessibility, was beginning its transformation into a wilderness open and waiting for people to explore it.

Goodbye to Schroon Lake, 1879

New York State Museum

Homeword Bound, Lake George, 1879

New York State Museum

Automobiles

Perhaps the system with the greatest impact, however, were the automobiles. As cars became cheaper and more mainstream, extensive highway systems were created, including in the Adirondack Park. Visitors to the Park thus capitalized on the greater accessibility of the region's natural wonders and flocked to the Adirondacks in their combustion-based vehicles. Seemingly not in keeping with his conservation efforts, Stoddard actually helped this transition to a more visitor-friendly mode of transportation by creating and selling detailed auto-road maps of the Adirondacks. He actually viewed the automobile as good for the economy because "the people who bring expensive cars and drivers up [to the Adirondacks] are the kind who contribute most to our support by their liberal expenditures" (Stoddard's Northern Monthly, 1908, p. 112). Stoddard essentially sought to increase traffic throughout the area, expressing hopes to "convince auto owners that Placid is the best center in Northern New York from which to make attractive excursions with their cars" (Stoddard's Northern Monthly, 1908, p.112). I wonder what Stoddard might think of ATVs these days!