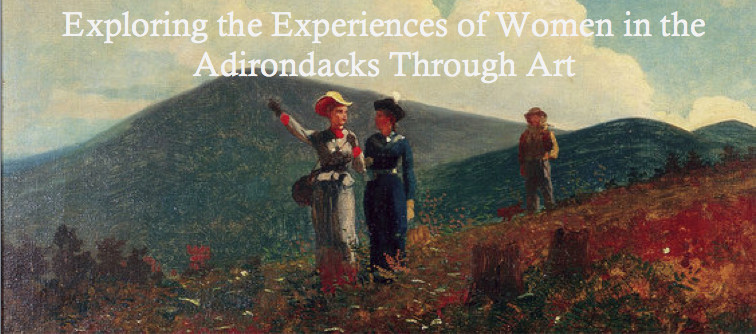

The theme of cooking in regards to women’s domestic role also appears in a lithograph published by Currier & Ives at an unknown date, but likely in the 19th century. Currier & Ives was a popular lithographic firm that illustrated and disseminated scenes of current events, political figures, and American life in the 19th century and was a major publisher of Adirondack scenes, and as such, is a significant primary source. The colored print Among the Pines. A First Settlement depicts a small log house under construction on the right side of the picture plane and four figures in the center, a man with a gun and a dead deer at his feet, a woman, and two children. In the background are two men hunting in a dense forest of pine trees. Beside the woman is a boiling pot suspended over a fire by a pyramid of sticks. This setting as well as the cabin seems much more modest than the previous setting of Interior of an Adirondack Shanty. In this print, we see documentation of the life style that many Adirondack settlers characterized as “toughing it.”

As Schneider reports, throughout the 19th century, the phrase “toughing it” broadly characterized the harsh quality and rigorous toils of daily life. In her account of her homestead, Mrs. Adolphus Sheldon states, “After I married we moved across the valley westward where we had to tough it. I had toughed it at my father’s and now I had to tough it here. There we lived for five years without a stove or fireplace. We absolutely had no chimney. We burned wood right against the logs of the cabin and when they got afire we put it out. We lived, you might say, on work and love,” (Schneider, 100). The lifestyle that Mrs. Sheldon describes is paralleled in this print.

The appearance and actions of each figure in the scene are very telling of their social roles. The father, dressed in a blue jacket, has just killed the deer, which he presents to his wife. The wife, donning a pink smock and a white apron, gestures to the deer and will likely begin to prepare it for cooking. To the right of the father and mother are the son and daughter, who wear corresponding colors to their parents, the boy in blue, and the girl in pink. The son touches the dead deer, mimicking his father’s action, which is representative of the man’s chief responsibility to provide. The young girl stands with her hands clasped, as if waiting for instruction. Here, we see the mother and daughter as supportive figures, those who prepare the meal after the man has procured the meat.

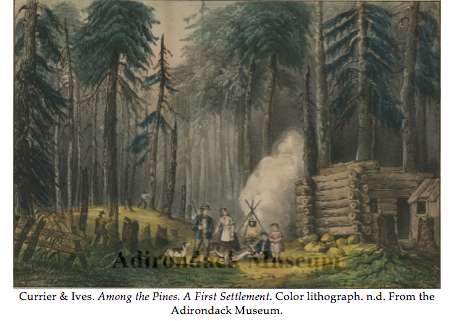

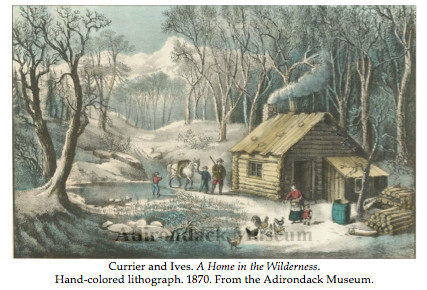

In another print by the same publisher entitled A Home in the Wilderness, printed in 1870, we see that the artist has made a similar visual distinction between mother and father and daughter and son. In the scene, the mother and daughter stand side by side feeding the chickens. This small-scale farming and animal care is a distinctly female activity. In addition, the mother and daughter wear clothes in the same shade of deep pink. Smoke streams from the chimney indicating that the mother may be baking something in the woodstove. The woman looks to her right at the man, who has just arrived after hunting in the forest with his game on the back of the horse. Next to him stand his two sons, who likely participated in the hunting ventures. The mother and daughter occupy the far right side of the picture plane while the father occupies the center of the picture plane as the primary focus. In addition, the young boys stand in proximity to their father and far away from their mother. Here, like in the first print, we can infer that there is a strong theme of gender present in this scene. While the mother and daughter are preoccupied with their small-scale farming, the father and sons have hunted to procure meat as the primary action figures in the scene. Arthur Fitzwilliam Tate presents a similar scene in Arguing the Point, in which the mother calls from the cabin, beckoning the men to come for dinner. The child mimics her mother's actions, pulling at her father to come for dinner.

In another print by the same publisher entitled A Home in the Wilderness, printed in 1870, we see that the artist has made a similar visual distinction between mother and father and daughter and son. In the scene, the mother and daughter stand side by side feeding the chickens. This small-scale farming and animal care is a distinctly female activity. In addition, the mother and daughter wear clothes in the same shade of deep pink. Smoke streams from the chimney indicating that the mother may be baking something in the woodstove. The woman looks to her right at the man, who has just arrived after hunting in the forest with his game on the back of the horse. Next to him stand his two sons, who likely participated in the hunting ventures. The mother and daughter occupy the far right side of the picture plane while the father occupies the center of the picture plane as the primary focus. In addition, the young boys stand in proximity to their father and far away from their mother. Here, like in the first print, we can infer that there is a strong theme of gender present in this scene. While the mother and daughter are preoccupied with their small-scale farming, the father and sons have hunted to procure meat as the primary action figures in the scene. Arthur Fitzwilliam Tate presents a similar scene in Arguing the Point, in which the mother calls from the cabin, beckoning the men to come for dinner. The child mimics her mother's actions, pulling at her father to come for dinner.

While the majority of illustrations of women’s domesticity involve cooking, women conducted a vast number of other activities that were also essential for survival in the early years of settlement in the Adirondacks. Flavius Cook, the town historian of Ticonderoga wrote in his 1858 Home Sketches of Essex County, that women “picked their own wool, and carded their own rolls, and spun their own yarn, and drove their own looms, and made their own cloth, and cut their own garments, and did their own making and mending…and dipped their own candles, and tried their own soap, and bottomed their own chairs, and braided their own baskets and wove their own carpets, and quilted their own coverlids, and picked their own geese feathers, and milked their own cows, and tended their own calves and pig-pens, and went a visiting on their own feet, or rode to meeting or wedding on ex-sleds with a bundle of straw for a seat, and at their backs two hickory stakes and a long chain,” (Schneider, 99).

While the majority of illustrations of women’s domesticity involve cooking, women conducted a vast number of other activities that were also essential for survival in the early years of settlement in the Adirondacks. Flavius Cook, the town historian of Ticonderoga wrote in his 1858 Home Sketches of Essex County, that women “picked their own wool, and carded their own rolls, and spun their own yarn, and drove their own looms, and made their own cloth, and cut their own garments, and did their own making and mending…and dipped their own candles, and tried their own soap, and bottomed their own chairs, and braided their own baskets and wove their own carpets, and quilted their own coverlids, and picked their own geese feathers, and milked their own cows, and tended their own calves and pig-pens, and went a visiting on their own feet, or rode to meeting or wedding on ex-sleds with a bundle of straw for a seat, and at their backs two hickory stakes and a long chain,” (Schneider, 99).