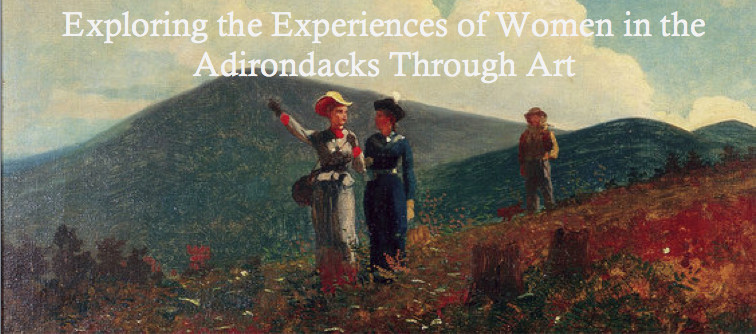

Hiking was considered an activity exclusively for men, but there are a handful of women credited with climbing mountains in the 19th century in spite of the criticism they received. There are several paintings that depict women hiking and climbing mountains in the Adirondack Museum's collection, proving that although this activity was frowned upon, artists nevertheless found it to be an interesting subject worthy of painting. In Edward Lamson Henry’s The New Woman, an oil painting completed in 1892, we see two women hiking with a guide standing behind them. Lamson, in contrast to many sportsmen of the time, paints these women in a positive light, and makes them the main focus of the scene while the guide stands in the back as a secondary figure. The women are situated in the foreground of the painting with more distinguishable features.

In contrast, the guide stands far in the background of the picture plane and has less distinct features as Henry successfully employs atmospheric perspective. The woman dressed in grey points outwards as if relaying to her friend that they should continue in that direction. Although a guide accompanies them, these women embody independence and freedom. The title The New Woman is praiseworthy in its own right, as the artist applauds the newfound assertive nature of the “new woman.”

While Henry seems to find no fault with women taking up the activity of hiking, many sportsmen criticized and actively discouraged women from recreation. They often relayed stories about the dangerous wilderness in order to frighten any woman who wished to explore the Adirondacks. Lucia Pychowska, who climbed Mount Marcy with her brother, discusses the exaggeration surrounding the black fly in an article in the Continental Monthly in December 1864. She stated that “we had heard so much of this pest, and seen so little of him, that we began to think his existence somewhat mythical, in short, a traveler’s tale, invented by men to keep women from venturing beyond the well-beaten track of ordinary journeying,” (Weber, 81).

However, several women, such as the ones depicted in this painting, ignored any criticism thrown at them and climbed many mountains in the Adirondacks. In preparation for her book, Sandra Weber came across an old account of a young farm girl named Esther McComb, who aspired to climb Whiteface Mountain (Weber, 12). Esther was not hindered by comments like “’girls should be spinning and baking’” and made her way to Whiteface in 1839 (Weber, 12). However, she became lost in the woods and instead of climbing Whiteface, she discovered a new mountain, which would be called Esther Mountain. And in 1859, Hattie Wadhams successfully climbed Whiteface. Many of these excursions also attracted groups of women and in 1850, Anna Constable and her friends camped in lean-tos in Raquette Lake and then hiked up Blue Mountain.

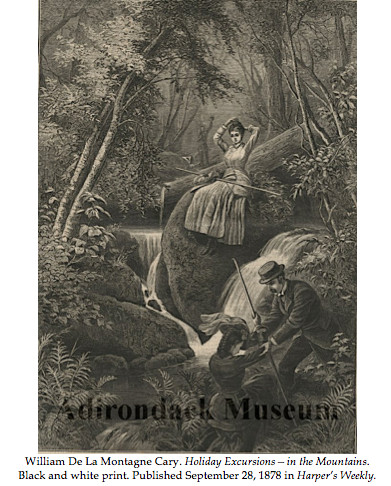

In William De La Montagne Cary's Holiday Excursions--In the Mountains, we see a very different illustration, although there are also women hiking in it as in the previous painting. While Henry similarly presented a male figure in his painting, the guide was far in the background and the independent women were the primary focus of the scene. However, in Cary's print, we see a man helping a woman climb up a boulder. Presumably, he has just helped the other woman, who rests on top of a mossy boulder above the spring. Here, there is a strong sense of the superiority of the man as he assists the woman. In addition, the woman whom he helps has her back faced to the audience. In effect, her individuality and identity is visually lost through this positioning, which is a notion that can also be understood thematically. The woman who sits above on the boulder is preoccupied with fixing her hair, which would have been a necessary concern for a woman in the presence of a man. In addition, both woman wear more fancy dresses than in the previous painting as well as have noticeably stylized hairstyles. For instance, the woman with her back towards us has a complicated braided loop hairstyle and a hat complete with flowing ribbons. This would have been a much more acceptable recreational activity as the women are adhering to the clothing customs of the period as well as are being escorted and assisted by a man.

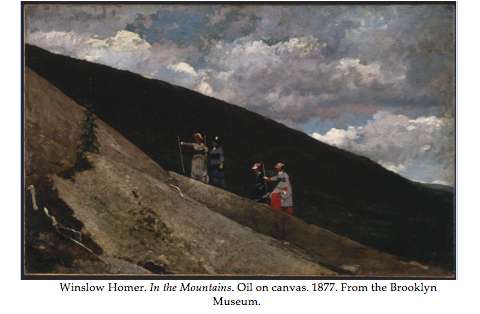

In Winslow Homer’s In the Mountains, an oil painting done in 1877, we see four unaccompanied women hiking up a fairly steep slope. The actions of these women would have been condemned as indecent and dangerous, especially because they are unescorted. Each of the women holds a walking stick and they all wear dresses and caps, likely made of straw or felt. The strong upright position of the woman in grey implies a certain fortitude and determination, which were characteristics that the handful of women who hiked in the 1800's embodied.

In a reflection of their adventurous attitudes, many women began to alter their clothing to better suit their hiking purposes. In 1896, Lucy Bohrman ascended Mount Marcy and stated “Helter skelter, off with silks, kid gloves, and linen collars, on with bloomers, stout boots, and felt hat, and we helpless women are transformed into helpful human beings,” (Weber, 83). Helen Lossing climbed Mount Marcy in 1859 wearing a petticoat and a hooded cape that she adjusted and customized to make her ascent easier. She sewed buttons onto her dress so she could raise it when she needed to climb a steep hill. Some women wore these alterations even when they weren’t hiking, but merely going about daily life. Blanche Isham, in The History of Keene Valley Congregational Church, commented that many tourist women attended church wearing “ankle length skirts and tin cups on their belts,” (Weber, 81). In addition it was believed to be “a good habit of the ladies in the Adirondacks to wear pretty hunting knives or daggers in their girdles,” (Weber, 83). Some men even began to think more practically about women’s hiking dress. Benson Lossing, an author and historian, wrote of women’s appropriate hiking attire “A woman needs a stout flannel dress […] a hood and a cape of the same materials, stout calfskin boots that cover the legs to the knee […] and an India-rubber satchel for necessary materials (Weber, 80).