Industry and Development

As the Adirondacks became less unfamiliar to people over time, the desire to conquer them became more prominent. Settlers started to develop land, building towns around rising industries. The area was first used for trapping and hunting, and later for logging and mining. The tourism industry also promoted the development of land; grand hotels and camps were built for the upper class as a way to escape the city life. All of these activities enforced the idea that humans not only had the right to wilderness, but that they did not owe it anything. When the land was used or altered to meet human need, people did not have to compensate for their impact. Instead, the general opinion was that the park was there to serve them, and they did not need to attach any intrinsic value to it. These views are reflected in artwork that focuses on humans rather than the wilderness, which can be found throughout Adirondack history.

Hunting and Trapping

Trappers and hunters were some of the first people attracted to the Adirondacks, drawn to the mountains for game. Native populations lived mostly in the lowlands surrounding the park, commonly venturing further inward to hunt (Schneider 16). When Europeans began to arrive in the Adirondack region, they quickly started trading with the natives, and the demand for beaver pelts rose drastically. The fur trade became a more dominant industry and animal populations were overexploited (Jenkins 44). As settlers found a home in the park, hunting persisted, and even today, trappers can be found in the area. Some artwork looks at how trappers and hunters viewed the land, and it considers their use of the park as both a resource and a home.

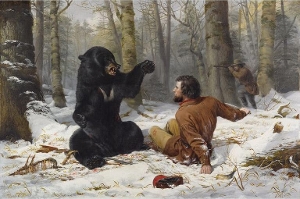

Painters such as A.F. Tait chose to focus on the sport of trapping/hunting and wildlife from the 1850s to the 1880s in the Adirondacks. For example, his painting A Tight Fix: Bear Hunting in Early Winter (1856, upper left) depicts a dramatic scene between a man and a bear about to fight, the man’s face pictured in a state of concentration and determination while the bear claws the air in front of him (The Adirondack Museum 30). Another one of Tait’s paintings, Mink Trapping in Northern New York (1862, upper right), was praised as one of the first accurate representations of mink trapping, showing two trappers gathering the animals they had caught (The Adirondack Museum 40). Both paintings include trappers and hunters using the Adirondacks for its wildlife, demonstrating how these activities were once considered a legitimate and more respectable profession. Trappers and hunters depend on the land as a resource, and from their point of view, they have the right to exploit—and even overexploit—animal populations. Modern regulations control animal populations more strictly, but historically, animals such as the wolf, cougar, and eagle were extirpated before the 20th century. However, for most trappers and hunters, the area is seen as not only a hunting ground, but also a home. To them, the Adirondacks are essential to their way of life.

Logging

Loggers began to enter the Adirondack Park in search of lumber, thinking of the forests as a resource and hardly considering the impacts of their actions. The logging industry slowly grew until changes in demand and technology allowed New York to surpass Maine as the most important and successful lumber state in 1850. The industry first harvested the Adirondacks for white pine because the tree grew near rivers and loggers were able to float it down to sawmills. Next, loggers cut for spruce since it could also float, and water was the only way to transport lumber (Schneider 202-203). When new technology created a process during which wood pulp could be made into paper, lumberjacks cut the Adirondacks for any softwood that could float (Terrie 107-109). Then, when workers built railroads through the park, hardwoods could finally be cut and transported by rail car. This growing interest in the Adirondacks as an industrial center and resource pool was reflected in many different types of artwork throughout Adirondack history.

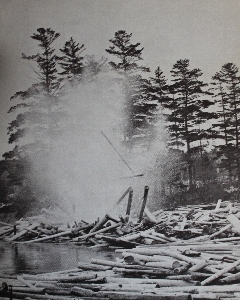

Photographers such as Jim Fynmore captured the essence of the industry in his work during the later part of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. He remarks “The lumberjack is still the strong, rugged individualist who loves picturesque clothing or an occasional test of his athletic ability. Human beings cannot be mechanized, at least in the lumber camps,” which views the profession as one of passion and excitement, as something that cannot be replaced (Fynmore). His photo "BOOM! Dynamiting a Log Jam" (upper left) shows logs flying up in the air after men used explosives to release the logs piled up on a river. In "New Woods Road," (upper right) Fynmore photographed lumberjacks building a road with tall piles of logs scattered throughout the woods, showing the direct impact of the industry on the forest (Fynmore). Fynmore’s images of the logging industry show the vast amounts of timber taken from the Adirondack Park and, in turn, document the depletion of another natural resource. To lumberjacks, the Adirondacks were a source of wood to be cut, and once an area had been cleared of the desired species, it was no longer useful and the men moved on. Lumberjacks constantly set up and tore down camp while on the job because once an area was cut, they were forced to move on. Though they inhibited the forest for a long period of time, they were ultimately just passing through.

Development of Land

Originally, only the rich could afford to vacation in the Adirondacks, viewing the area as an escape from the hustle and bustle of city life. When towns within the blue line realized that they could make money off of hotels and other tourist necessities, the industry began to grow and the Adirondacks became more accessible to a greater number of people. The construction of roads within the park and the spread of automobiles meant that the average family could now explore the wilderness within the span of a day. With time, it was easier to drive through, climb a mountain or two, and drive back home at the end of the day than it ever was before. These developments were shown quite literally in artwork that focused on the expansion of the tourism industry, documenting the trips people made to the area.

Henry M. Beach, a photographer in the early 20th century, captured some of the family-run camps, hotels, and clubs of the time period in his work. Pictures like "View from Burdick’s camp" (1907, upper left) and "Wawbeek Hotel dining room" (1912, upper right) show the extent of some of these venues. View from Burdick’s camp looks out over a lake dotted with canoes and people using it for various forms recreation (Bogdan 79). "Wawbeek Hotel dining room" displays the expensive and exquisite nature of some of the hotels within the park, depicting a lavish room set with fine china and candles (Bogdan 93). Photos like these support the idea that tourists are attracted to the Adirondacks for a few main reasons: they seek recreational activities, they want a break from a more urban lifestyle, they want to get in touch with nature, or they want to get in touch with themselves. Tourists tend to use the area to their own benefit, commonly leaving a negative impact on the park through increased foot traffic, litter, and pollution. However, they do bring in a lot of money to the park, which helps to preserve and protect the land. Regardless, the average tourist passes in and out of the Adirondacks, usually unaware of the long-term consequences of the industry.

Works Cited

The Adirondack Museum. A. F. Tait: Artist in the Adirondacks. Blue Mountain Lake: The Adirondack Museum of the Adirondack Historical Association, 1974. Print.

Bogdan, Robert. Adirondack Vernacular: The Photography of Henry M. Beach. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003. Print.

Fynmore, Jim. The Central Adirondacks. Prospect: Prospect Books, 1955. Print.

Jenkins, Jerry. The Adirondack Atlas: A Geographic Portrait of the Adirondack Park. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2004. Print.

Schneider, Paul. The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1997. Print.

Terrie, Philip G. Contested Terrain: A New History of Nature and People in the Adirondacks. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997. Print.

Image Sources (in order of appearance)

Banner courtesy of: Amanda Lodge (original photo)

A Tight Fix: Bear Hunting in Early Winter courtesy of: http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=141949

Mink Trapping in Northern New York courtesy of: http://www.houzz.com/photos/11237567/Arthur-Fitzwilliam-Tait-Mink-Trapping-in-Northern-New-York-Print-traditional-artwork

"BOOM! Dynamiting a Log Jam" courtesy of: The Centeral Adirondacks by Jim Fynmore

"New Woods Road" courtesy of: The Centeral Adirondacks by Jim Fynmore

"View from Burdick's camp" courtesy of: Adirondack Vernacular: The Photography of Henry M. Beach by Robert Bogdan

"Wawbeek Hotel dining room" courtesy of: Adirondack Vernacular: The Photography of Henry M. Beach by Robert Bogdan