Early climbers in the Adirondacks such as Wiessner left iron pitons (long metal spikes) in their wake, pounding them into the cliffs. While these leave scars in the rock and sometimes cannot be removed, they were the only method that climbers of that era had of protecting a fall. These (very rusty) pitons and their scars can still be seen today, for the most part relics of a bygone era.

The “clean-climbing revolution” took place in the 1970s; instead of pitons, climbers placed nuts, hexes, and later spring-loaded camming devices as protection. These new inventions were easily removable, and did not damage the rock. Since then, local Adirondack ethic has dictated that fixed protection (bolts and pitons) may only be placed where removable protection is unfeasible (Lawyer, Haas 17).

These strict traditional ethics make the Adirondacks such a unique place to climb. To quote Dominic Eisinger in Adirondack Rock: “A common philosophy of minimizing human impact in the Adirondack Park is shared by the Adirondack climbing community and will help ensure that we maintain our freedom, which is by its nature individualistic and free-spirited.” Don Mellor summed up the wild and adventurous nature of Adirondack Climbing in the brilliant introduction to his guidebook: “What is climbing in the Adirondacks? It’s getting away. It’s figuring things out for yourself… Those who have gone before you have tried their best to hide their passage, not advertise it. This is an untamed place, even in many ways an inconvenient place” (Mellor 13).

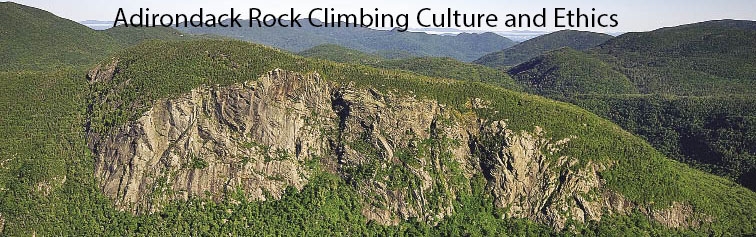

The harsh and unforgiving nature of the Adirondack mountains and the strong leave-no-trace ethics have resulted in a climbing culture that values boldness, adventure, and most of all respect for the land. While the Adirondacks feature some easily accessible roadside crags, it is the towering wilderness cliffs such as those on Wallface and Gothics that set the region apart from others in the east. Climbers have valued this aspect of Adirondack climbing since the days of Fritz Wiessner: “There is a charm to Wallface, as to all Adirondack rock climbs. It is the charm of solitude. It is beautiful, remote, wild country” (Wiessner). In the heart of the High Peaks Wilderness, things have not changed. These days, Kevin MacKenzie, Adam Crofoot, Scott Van Laer, and others are still putting up bold first ascents in Panther Gorge, a tough 8-mile hike and bushwhack away from civilization.