Although potatoes are an essential component of the pitepalt, kroppkaka, and raspeball, there are some differences in the way the potatoes are integrated into the dough of these Scandinavian dumpling varieties. Typically, crushed potatoes are shredded or grated and mixed with the specific grain to make a firm dough; however, in the case of the rasepball, the potatoes are often boiled in advance, giving them a lighter color compared to dumplings made from raw potatoes4.

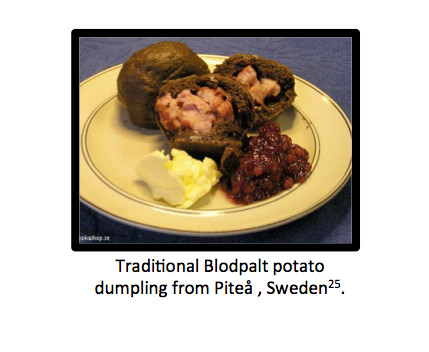

There are also differences in the grains of the flour for each potato dumpling variety. The rasepball and pitepalt traditionally contain predominantly barley, which is the oldest grain in Scandinavia, cultivated predominantly in the Northern regions4. Alternatively, the Kroppkaka contains flour made from wheat, a grain historically grown in southern Scandinavia following its initial cultivation in Sweden around 1500 (the pitepalt also sometimes contains wheat flour, but mixed with barley as well)4. Interestingly, the specific traditional flour contents in the dough are consistent with each dumpling’s historic region of origin, as the pitepalt and rasepball (containing predominately barley) originated in the northern cities of Piteå, Sweden and Bergen, Norway, respectively, while the kroppkaka (containing predominantly wheat) originally comes from the southern island of Öland, Sweden. Typically salt and pepper may be added to the flour, and some recipes now contain eggs in the dough8. During the late middle age, rye became a popular grain grown in southern Scandinavia, and today rye can be found in some potato dumpling recipes as well4. In particular, the dark-looking blodpalt, a close regional cousin of the pitepalt, often contains rye flour24. The blodpalt gets its name from a distinctive Scandinavian ingredient found in the recipe: blood, which is often mixed right in with the flour of these peculiar dumplings4. For centuries, the Swedes have employed pig’s blood in other recipes, such as those for broths and sausages4. Similarly, the nomadic Sámi communities in northern Scandinavia have prepared blodpalt for nourishment throughout the long, barren winters for hundreds of years using reindeer blood24. Unlike the Swedes, who always harvested the blood right after the animal was killed, the Sámi learned to freeze-dry the blood and grind it into a powder that could be preserved and transported as they migrated throughout the Sámpi territory4.