While the type of space being protected is different in terms of size, the way the two structures are employed in doing so is quite similar: they both are used dynamically to address threats.

The major commonality between these two structures is both rely on using their space and their structures to garner their strength once the enemy has chosen their approach and it allows them the flexibility for quick change. This allows them from a defensive, fortified position to make offensive maneuvers despite being the ones under attack. The only variation between the strategic use of the Great Wall versus Himeji-Jo is the scale on which it takes place. Given the scope of the Great Wall of China a standing army, the first in world history, was required in order for it to operate properly. In contrast, Himeji-Jo Castle only required a fraction of the soldiers, which makes sense since it is only a tiny fraction of the space in comparison. Disregarding scale, however, it is clear that these two differing forms of fortification attempt to accomplish the same task, using technique that emphasized the importance of maneuverability.

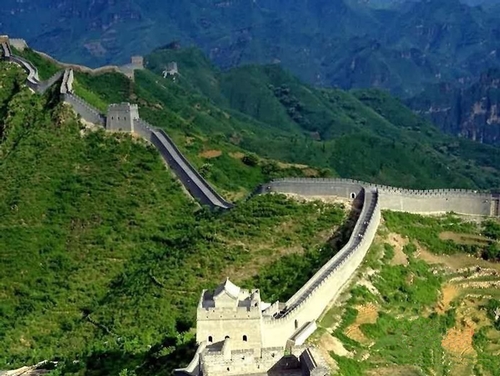

The Great Wall

The Great Wall of China is not a fortification that the Chinese thought was impenetrable. Rather, it was something that made life much more difficult for their enemies and much easier for themselves (Great Wall of China). The Great Walls first function was as an early warning system (Geil, pg. 95). Once a threat was identified, signals and messengers could be employed to get the message to army camps standing by away from the lines about the impending attack. Along the Great Wall are defensive stations, towers, where wall defenders could retreat to if overrun (Great Wall of China). The stairways of these towers are constructed in a way that made them restricted and confusing. Thus, making it difficult for enemies to gain a good sense of direction.

Himeji-jo Castle

One of the major design aspects of Japanese castles was to make the approach to the keep as difficult as possible and many scholars point to Himeji-Jo as a perfect example of this element (Turnbull, pg. 144). As the illustration below demonstrates, the approach to the keep is very windy and would cause forces to bottleneck at multiple points along the suggested route. Another significant aspect of these inner and outer courts is that each of these successive spaces is arranged in a way so that any line of defense captured by an enemy could readily be recaptured from the area inside it while also allowing the defenders to observe all (Turnbull, pg. 152).