Lake Champlain hosted one of the most militarily strategic regions during the Revolutionary War and hosted the birth of the United States Navy. In 1775, military plans for Lake Champlain were being developed even before the first shots at Lexington were fired, igniting the Revolution in April (Sails and Steam, 116). The revolutionaries recognized the strategic significance of the lake, due to its access from the north through Canada, which was heavily fortified by the British, via the St. Lawrence Seaway and Richelieu River. The British could eventually pass through waterways to Albany and New York from that direction. The first military act on Lake Champlain was the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Benedict Arnold’s troops and Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys on May 10, 1775 (Sails and Steam, 117). Soon after its capture, the Continental Congress wanted to abandon it and Crown Point, but although Arnold and Allen disagreed on nearly everything, both persuaded the Congress to keep the forts. (Chronicles 193). In a letter, Arnold stated, “Ticonderoga is the Key of this every extensive Country, & if abandon’d leaves a very extensive Frontier Open to the Ravages of the Enemy” (Memorandum Book, 71). The Congress agreed to send troops to reinforce the forts (Chronicles, 193). Soon, plans were drafted to invade Canada to prevent any British incursion into the Colonies from the north (Chronicles, 194). To embark on such a mission, the United States needed a navy.

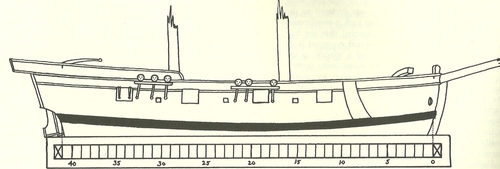

Reconstructed lines of the “schooner” Liberty, from Millar, Early American Ships, 130. Millar reconstructs her dimensions as 48' length on the keel, 41' length on the deck, and with a beam of 14'. Note the “pink” stern he has given her.

Soon after the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, a regiment that had separated from the Ticonderoga raiding party captured a schooner at Skenesborogh (present day Whitehall, NY). This was renamed the Liberty and was the first vessel of the United States Navy. The Liberty was sailed north to Ticonderoga, and gained Arnold as its captain on May 14 (Sails and Steam, 117). Seemingly like a child wanting to play with new toys, Arnold immediately embarked north to St. Jean, Quebec, where the British had a fort. The Americans arrived to find only 14 British soldiers manning the fort, who immediately surrendered. The commander had been on a supply run to nearby Montreal with many men. When he returned, he found his sloop, all provisions, and weaponry missing (Sails and Steam 117). The Americans returned south under a “fine north gale” (Naval Documents, 1:358). With such luck the United States Navy then consisted of two vessels, the Liberty and the Enterprise. Upon return to Ticonderoga, Liberty received its first fixed arms of four cannons and eight swivels (Trumbull, 146). For many months thereafter, the two-boat fleet was used to patrol the lake while more ships were built and until further orders were given (Continental Army Schooner Liberty). In August, plans were executed for an invasion of Quebec.

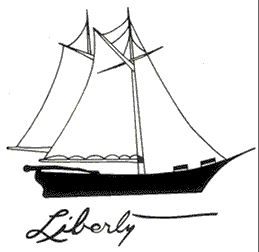

"Contemporary view of the Continental Army Schooner Liberty. Detail of a print found by S.H.P. Pell, taken from Howard I. Chapelle, History of the American Sailing Navy, Plate V."

The new four-ship American Naval fleet embarked for the invasion of Canada on August 28 in an effort to capture Quebec and prevent the British from attacking the Colonies through Lake Champlain. “The capture of Quebec…was critical to the American Cause” since it would reduce the vulnerability of the Colonies during the Revolutionary War (Sails and Steam, 129). The Americans successfully captured Fort St. Jean and Fort Chambly to the north; the naval fleet aided in the bombardment of these forts. However, after four failed attempts at capturing Montreal over two months, the Americans ceased attacking and resolved to encamp themselves at Fort St Jean and Fort Chambly throughout the winter, during which hundreds of troops died of illnesses induced by the extreme cold (Continental Army Schooner Liberty). The Americans decided to attack the more fortified Quebec City early in 1776 and were successful in capturing eleven British vessels fleeing to the city on the way. However, the Americans, camping along the St. Lawrence River were quickly ousted by a surprise attack of the American camp by 1800 British troops fresh from Britain in May, 1776 and burned most of the ships during their retreat. Upon return to Fort Ticonderoga, the Americans began rebuilding the Navy and preparing to defend against a large British incursion.

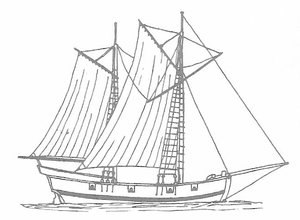

Another drawing based on the Pell print. There is no “pink” stern, but a long tiller. From the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum.

During the summer of 1776, the British and American armies frantically assembled navies and gathered troops. The British intended to attack Albany and meet up with another force that planned to attack New York. The Americans finished assembling their 15-ship navy and set sail on August 24, 1776. They initially moored themselves across the lake at a narrow pass at Windmill Point, near Isle-aux-Noix (Sails and Steam, 145). During the next month, Arnold moved his ships multiple times, and the Liberty was nearly captured by a surprise attack on the eastern shore by a group of 300-400 Native Americans. However on September 24, Arnold re-evaluated his strategy for the fifth time and finally decided to surprise the British from the southwest side of Valcour Island – in the present day Adirondack Park – and wait for the British there (ibid., 148). The prevailing winds on the lake during the summer and early fall were from the north and Arnold recognized that he could use this to his advantage. He planned for the British to sail past Valcour Island, where they would be south of the American fleet. Also, due to the narrow bay between Valcour Island and the western shore of Lake Champlain, only a few British ships could attack the Americans, but those British ships would be the subjects of the entire American force. However, the winds tended to shift from the south later in the fall.

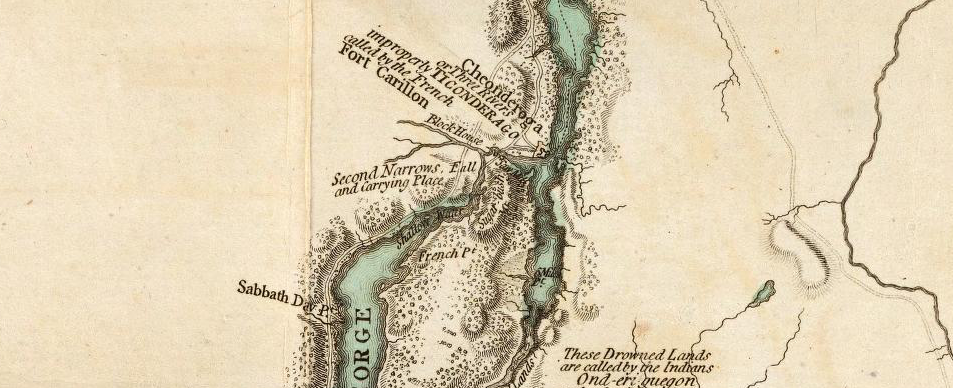

Region of Lake Champlain that Benedict Arnold first planned to defend against the British, Windmill Point is north of Isle La Motte

For another two weeks, the ships awaited the British and Arnold believed the British force, “by the best accounts, near equal to ours” (American Archives, 834). Little did he know, the British Navy soon to arrive was far larger than he could have imagined. On October 10, the Liberty left to Ticonderoga for provisions. At 8:00am October 11, the British Navy was spotted off Cumberland Head, just north of Valcour Island, where the British had been expecting the Americans based on erroneous reports from scouts. Two hours later, the British came around the southern tip of Valcour Island and Arnold received his first sight of the much larger, more experienced British Navy (Chronicles, 214). However, the American Fleet still had the tactical advantage, as the British experienced significant difficulty sailing against the strong north wind to fire at the Americans. The Americans were successful in fending off the British for many hours, although still sustaining significant damage. Also, throughout the day, Native American forces under the direction of British captains “menaced” the Americans from the western shore in the Adirondacks, where they had killed all local residents they could find (ibid., 216), testament to the hostility of the land at the time. The engagement lasted until 6:00pm, when firing ceased due to sundown (ibid., 217).

Drawing of the Liberty by Millar (Early American Ships, 129) from the Pell print. Note the “pink” stern.

Arnold decided to use their knowledge of the lake to make a risky, arguably audacious, retreat past the British Navy, moored south of Valcour Bay. Arnold ordered all available men to row through the night, towing the eleven remaining ships. They set off at 7:30 and bypassed the British Navy entirely undetected (Sails and Steam, 155). Overnight, the winds shifted to a strong south wind, which made rowing extremely difficult for the Americans, but sailing even harder for the British. Although the American fleet was widely dispersed over many miles south of Valcour, they were in relative safety. A few of the American ships sunk during the journey due to severe damage during the previous day’s engagement (ibid., 156). Throughout October 12, the Americans continued rowing down the lake while the British made little progress in pursuit. However, the next day, the wind shifted back from the north and while the Americans could now sail downwind, the British fleet soon caught up with them and forced many ships to run into bays and abandon (ibid., 157). Arnold and his remaining troops reached Ticonderoga early in the morning on October 14, without sleep for three days (ibid., 158). The British considered attacking Crown Point and Ticonderoga, but returned to Canada for the winter due to the hostile terrain on the western shore of the Lake and strong south winds for many days preventing them from reaching the forts.

The American Cause at Lake Champlain was heavily influenced by the weather and terrain of the region. The prevailing winds – and shifts – worked to the advantage of the Americans in multiple situations. Also, the cold winter in Canada severely weakened the American forces, while the prospect of spending the winter neat Ticonderoga was less appealing than camping in forts far north in Quebec was for the battered Americans in the winter of 1775-76, another testament to the hostility of the Adirondack region. Native Americans siding with the British made settlements on either side of the lake practically impossible. The unwelcoming weather and terrain of the Adirondack region significantly influenced this nation’s history. Had the weather been less cruel during the winter, Montreal could have been an American city – or the Revolutionary War could have been lost due to a British incursion dividing the colonies by Lake Champlain or the Hudson River. Had the terrain of the Adirondack Park been more habitable, Americans could have created more forts along Lake Champlain’s shores to defend against the British. These unique aspects of Lake Champlain set the stage for vicious battles and audacious military plans that led to the current establishment of the Lake Champlain Valley as part of the United States.

All non-map images and captions courtesy of the American War of Independence - At Sea website.